Long before Fannie Farmer, Betty Crocker, or Martha Stewart, Lydia Maria Child provided American women with tips and tricks for running a smooth household. Her most successful book, The Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy, was first published in 1829 and went through 33 editions. Though Child is often remembered for her domestic guidance, her literary legacy includes a heaping helping of activism. She became one of the most prolific and progressive female authors of the nineteenth century.

Born Lydia Maria Francis in 1802, she grew up in Massachusetts and Maine and preferred to go by Maria (with an emphasis on the i). She attended girls’ schools but her brother Convers Francis, a Unitarian minister, was responsible for much of her literary education. She became a teacher herself at age 18.

Lydia Maria Francis’ first book was a rather racy title for a nineteenth century woman. Hobomok (1824) was the fictional story of an interracial couple, white Mary Conant and Native American Hobomok. The book was initially published anonymously, written by “An American,” but it was so well received in the Boston area that eventually word of Francis’ authorship got out. It’s considered the first New England historical novel. We have a modern edition edited by Carolyn L. Karcher in the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, but you can read the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s first edition via Google Books.

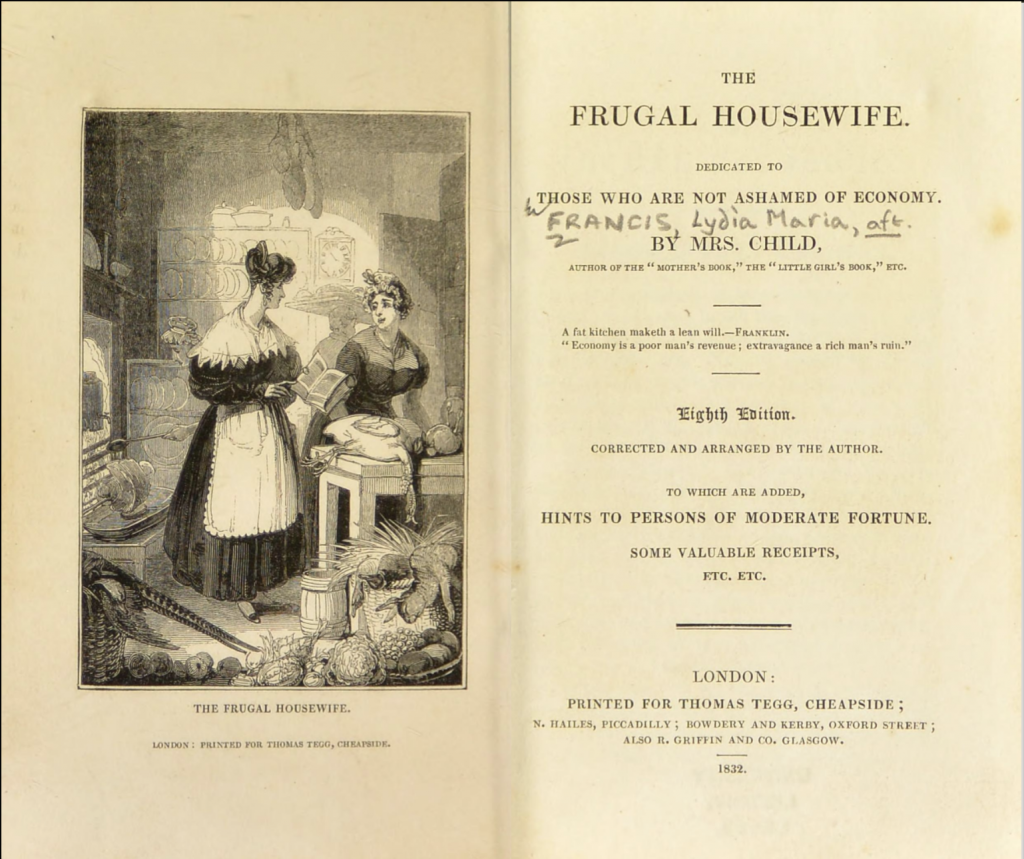

After Hobomok, Francis began to dabble in children’s literature. She founded and edited The Juvenile Miscellany, the first children’s periodical in America. The Juvenile Souvenir, a compilation of its stories, is held in our Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library. It was in 1829, one year after marrying lawyer and journalist David Lee Child, that she published her most successful book – The Frugal Housewife.

Writing The Frugal Housewife was almost out of necessity – David had debts and the couple needed money. Lydia Maria shared the domestic economy tips that kept their home afloat and, in doing so, made a bit of profit. The book was a hit, one of the most popular of its time. Our Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology holds a sixth edition of this book, not yet digitized, but you can read a first edition online from the Library of Congress. Other contemporary homemaking handbooks existed, but most were published in London for an English audience. Child had felt there was a particular need for an American-focused version. Eventually the title of her book was tweaked to recognize this distinction – The American Frugal Housewife. It was followed up by The Mother’s Book (1831).

As her books of household hints took off, Child turned her writing to issues of national importance – particularly, abolition and women’s rights. In 1833, she wrote An Appeal in Favor of Americans Called Africans. (We hold several copies of a 1968 edition from Arno Press.) Child supported immediate emancipation of enslaved men and women and is thought to be the first white American woman to do so in print. Following the publication of her Appeal, Child became increasingly active in abolition associations like the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Between 1833 and 1838, she continued to publish prolifically – more household guides and children’s’ stories, but also The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Nations and Ages (1835), and she continued contributions to the abolitionist paper The Liberator.

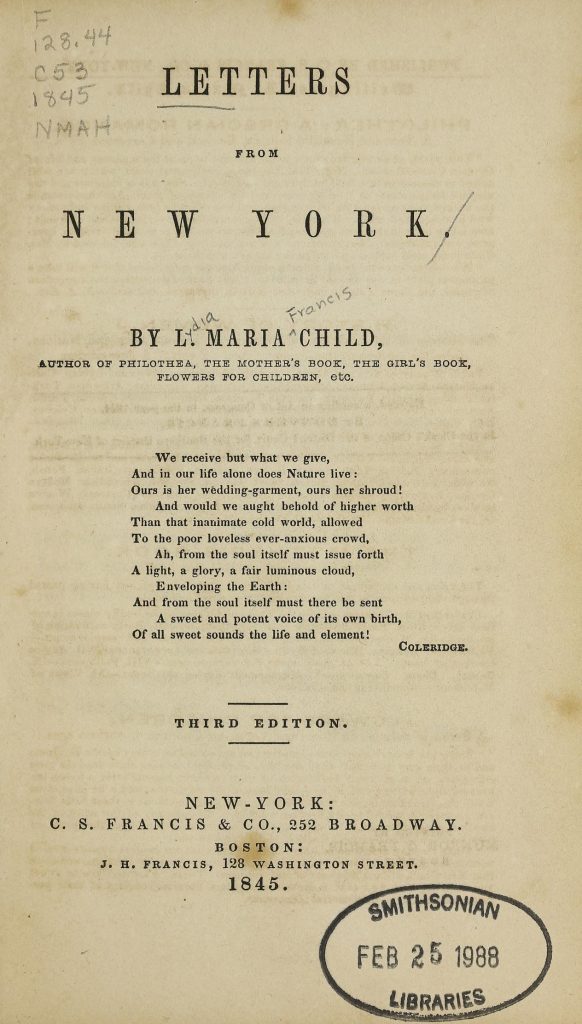

In 1841, with the couple still plagued by financial troubles, husband David was offered the position of editor at another abolitionist publication, the National Anti-Slavery Standard, which was the new newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society. He turned it down to focus on beet farming, but it was later offered to Lydia Maria, who accepted. On her own, she moved from the family farm in Massachusetts to New York. Child documents some of her time during this period in Letters from New York, a collection of her essays and correspondence from 1841-1843. The third edition of this work is now available in our Digital Library.

Though Child’s attention often focused on weightier causes, she did find time in 1844 to pen a popular poem you might recognize today. “The New England Boy’s Song About Thanksgiving Day,” also known as “Over the River and Through the Wood,” appeared in Flowers for Children, Volume 2. The nursery rhyme has evoked warm childhood memories of visiting Grandma’s house for generations of Americans. In her life, Child authored dozens of books and countless articles that not only entertained and educated but also advocated for the rights of women, enslaved persons, and Native Americans. She died in 1880 at the age of 78.

A compelling testament to Lydia Maria Child’s literary influence in the nineteenth century can be found in Art and Handicraft in the Woman’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. At the World’s Fair in 1893, the Woman’s Building held thousands of examples of the work and artistry of women. This book, available in our Digital Library, provides a glimpse of women whose contributions were well known in their own time but have since been forgotten in history books – women artists, writers, and scientists who are far from household names today. The Women’s Building at the Fair contained a library, filled with writings of both American and international women, as well as a special “New York Literary Exhibit” featuring women from that state. Child’s works, a total of 31 titles, were key among them. On page 117 in the commemorative book, Blanche Wilder Bellamy offered this accolade:

It is of interest to note that one of the few Afro-Americans connected with the World’s Fair, in an official way, is a member of the New York State Board of Women Managers, who volunteered to collect the works of Mrs. Child as a tribute from the blacks to her noble work in the anti-slavery cause.

Further Reading:

Baer, Helen G. The Heart is Like Heaven: The Life of Lydia Maria Child.

Carcher, Carolyn, L. The First Woman in the Republic: A Cultural Biography of Lydia Maria Child.

Child, Lydia Maria. Lydia Maria Child, Selected Letters, 1817-1880.

Clifford, Deborah Pickman. Crusader for Freedom: A Life of Lydia Maria Child.

Be First to Comment